Mention the aircraft company Douglas and most people think of the DC-3. There was however much more to Douglas with many military fighters, bombers and transports coming out of their Californian factories. But our story will just cover the ‘DC’ or Douglas Commercial series from the DC-1 to the DC-10.

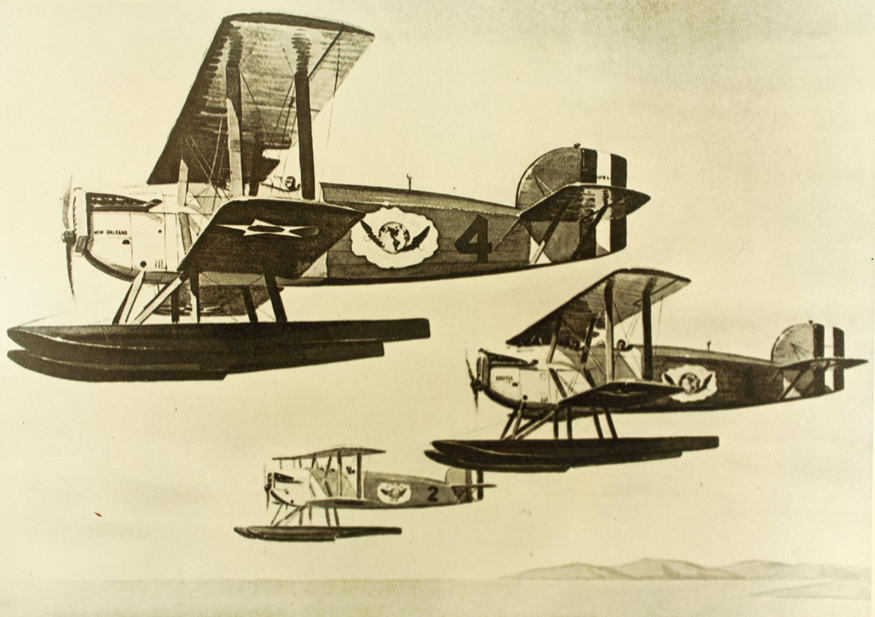

Founded by Donald W Douglas in 1921, the Douglas Aircraft Company produced aircraft under its own name until the merger in 1967 with McDonnell to become McDonnell-Douglas. 30 years later in 1997 the name disappeared for good when McDonnell-Douglas was taken over by Boeing. The first major Douglas success was the DT torpedo bomber some of which were modified for the US Navy into the DWC or Douglas World Cruiser and used by the Navy for the first aerial circumnavigation of the world in 1924. To commemorate this success Douglas introduced a new company logo of a plane flying around the globe.

Up to the early 1930s most airliners had been made of wood. Following a fatal crash in 1931of a Fokker Trimotor, the cause of which was thought to have been glue failure, the US authorities placed severe restrictions on wooden-built airliners; metal construction was the way forward. Boeing was first up with their 10 seat Boeing 247 twin-engine monoplane built for United Airlines who at that time also owned Boeing. TWA needed to compete but Boeing was too busy with the United order so TWA turned to the aircraft offered by Douglas, the DC-1 a 12 seat all-metal monoplane powered by two Wright 1820 engines.

TWA were very impressed with the aeroplane and after some modifications they took delivery of the sole example of the DC-1 in 1933 and placed a large order for the developed version to be known as the DC-2. By 1938 the DC-1 had been sold to Lord Forbes and found a new home in the UK. It later operated in Spain and was finally scrapped there in 1940 following a landing accident. The new DC-2 was a longer aeroplane with more powerful engines capable of carrying 14 passengers and first took to the air in 1934. This was a much more successful design than the DC-1 and 198 were finally built with US and European airlines such as KLM and Swissair buying the new Douglas. So impressed were they with their new aeroplane KLM entered one in the 1934 McRobertson UK-Australia air race finishing second behind the winning DH-88 Comet Racer.

If Douglas were happy about selling 198 DC-2s they would be over the moon when their next version the DC-3 came along in 1936. 607 DC-3s would be built but this number would be dwarfed by the military sale of the C-47 and C-53 variants 10,048 of which would take to the skies due to massive orders for aircraft to fight in the second world war. The DC-3 came about when American Airlines convinced Douglas to make a larger version of the DC-2 so it could carry sleeping berths for 14 people and would be known as the Douglas DST (Douglas Sleeper Transport). This redesign required the cabin to be made wider and it soon became apparent that with the sleeper berths removed 21 seats could be fitted instead. This version was called the DC-3. With the heavy demands for the military version Douglas ended civil DC-3 production in 1943 but not before the aircraft had proved itself to be a winner with the airlines and their passengers. In modern times it is still possible, I believe, to fly in a DC-3 on regular scheduled passenger service in two places, Canada and New Zealand. Many ex-military aircraft have been converted to civilian use and can still be seen popping up all around the world hauling freight. So popular are they in some of the more remote corners of the world there is a large market for airframes re-engined with modern turboprops. The ‘Dak’ will fly on for many years yet.

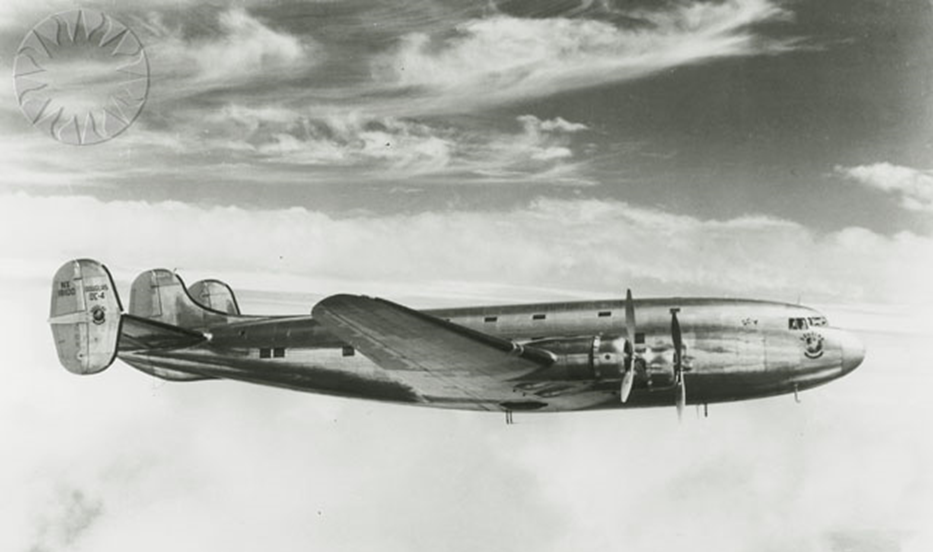

In 1938 Douglas designed and built the DC-4E at the request of several operators of DC-3s for a larger aircraft. The DC-4E (E for Experimental) could carry up to 52 passengers and was a four engine, triple-tailed aircraft similar to Lockheed’s Constellation. The DC-4E had many new innovations such as powered flying controls, an AC electrical system and pressurisation. However problems with these new systems and the inability to live up to its promise saw the design cancelled in favour of a less radical redesign. Only one DC-4E was built and ended up being sold in Japan who then reverse engineered it to build their second world war Nakajima G5N bomber.

From the ashes of the DC-4E design and flying just four years later in 1942, came another Douglas world beater the DC-4. As the British aircraft industry concentrated on building fighters and bombers for the war effort the US manufacturers were left to gain a massive lead in the design of modern airliners. This would be clearly demonstrated when post war BOAC and BEA were forced to order several American types as no British equivalent was available. Douglas had accrued several orders from airlines for this unpressurised airliner but before they could be delivered the US government, following the US entry into the second world war in 1941, took over all production for the military version of the DC-4, named the C-54 Skymaster or for the USN the R5D. 1,163 of these military versions were produced and flew not only in the second world war but also during the Berlin airlift being the mount of the ‘Candy Bomber’, Gail Halvorson. C-54s flew on with the military until 1972. Civil production of the DC-4 began again after the war and another 79 aircraft were built with the last one being delivered in 1947 to South African Airways. Popular with the charter airliners, many of the DC-4/C54/R5D fleet ended their days hauling cargo or being converted into fire bombers. Very few remain active today but just down the road from us at Duxford there is a group at North Weald breathing life back into an old USAF C-54 Skymaster.

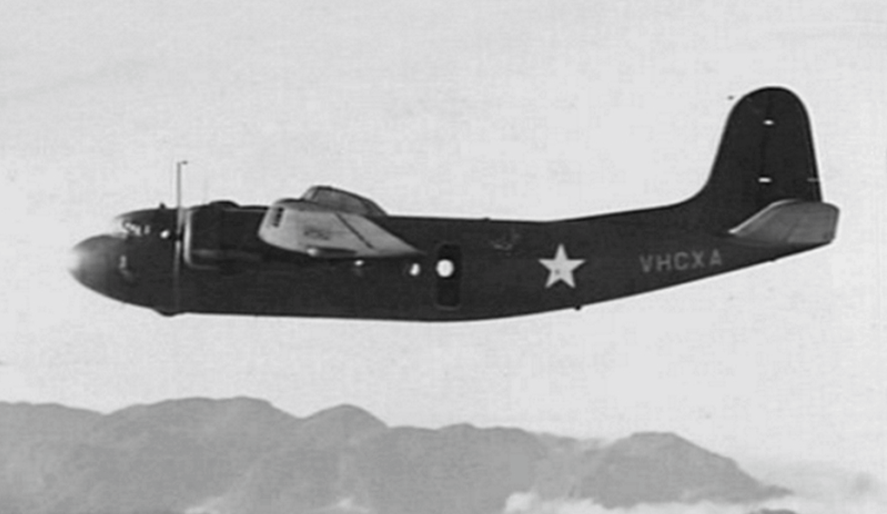

The DC-5 was a design intended for shorter routes than the DC-3 or DC-4 were flying. A twin engine 16-22 seater that first flew in 1939, the prototype actually became the personal transport of Bill Boeing, Douglas’ great competitor! The DC-5 came along at the wrong time as the world was slipping into war and airlines were not ordering new aeroplanes. Douglas was heavily committed to the US war effort and only 12 examples were built. KLM received four and the rest went to the US military. After the war the last surviving DC-5 was sold to an Australian airline who illegally smuggled it to Israel for use by their Air Force. It was finally scrapped in 1955.

By 1944 the US military approached Douglas asking for a bigger, pressurised version of the DC-4 based C-54 transport, however by the time the prototype flew in 1946 the war was over and the military withdrew its interest. Douglas however thought they were on to something and modified their design for civil use and named it the DC-6. The airlines loved the new aeroplane. The type was the aeroplane of choice for many transatlantic operators such as Pan Am. Sales were brisk, helped by Douglas offering several variants - passenger, cargo or combi mixed cargo/passenger aeroplanes. By the time of the Korean war the military renewed their interest and bought 167 of the DC-6 under the name C-118 Liftmaster for the Air Force or R6D for the US Navy/Marines. By the time production ceased in 1958 704 examples had been built. Once again many examples ended their days hauling freight. Several indeed continue to do so today, mainly in Alaska.

Douglas had one more throw of the propliner dice when American Airlines asked them for a version of the DC-6 that could fly coast to coast USA in under eight hours, as eight hours was the maximum duty day allowed for the flight crew by the FAA. Douglas wasn’t really interested until American offered to order 25 examples for a $40 million price tag. With a longer fuselage than the DC-6 and powered by four Wright R3350s, the most powerful engine available, the design was designated the DC-7 first flying in May 1953. The later DC-7B had more power again from uprated R3350s plus addition fuel tanks in the engine nacelles. This allowed South African Airways to fly Johannesburg to London with just one stop and Pan Am to fly non-stop across the Atlantic, at least eastward, westward still occasionally needing a refuelling stop. Douglas overcame this with the introduction in 1956 of the DC-7C which had a lengthened wing and fuselage and additional fuel tanks. Pan Am could now fly non-stop both ways and to compete BOAC were forced to buy the American airliner rather than wait for the Bristol Britannias it had on order to enter service. SAS also ordered the big Douglas and used it on their trans-polar routes to the States and Asia. The passenger life of the DC-7 was short as the Comet and Boeing 707 were soon snapping at its heels and from 1958 they were on the Atlantic route. The era of the big prop transatlantic airliner had gone.

The DC-7 and its complicated engines was a difficult and expensive machine to keep flying and after the major airlines started to dispose of their fleets the DC-7 did not see the same ‘after market’ use as the DC-6. Some did get converted into freighters and fire bombers but most of the 338 built were scrapped.

With the US military already flying jets you would think the writing was clearly on the wall for the piston engine airliners but the US airlines were not interested in any jet proposals put to them by Boeing. That company however was convinced the USAF would need jet tankers for their jet bombers so started work on what was to become the Boeing 707. Douglas meanwhile had briefly looked at a jet airliner design back in 1952. It was not until the USAF did indeed post a requirement for a jet tanker in 1954 that interest in a jet was renewed. However at the time of that posting Boeing was only a matter of months away from the first flight of its 707 jet transport and the USAF awarded them the contract.

Douglas decided to continue with its new jet now named the DC-8 but the airlines were very lukewarm about ordering this new generation of airliners. The breakthrough came in 1955 when Pan Am startled the airline world by ordering 20 Boeing 707s and 25 Douglas DC-8s. Frightened of being left behind, the other airlines started to place orders for the new jet as well. By the start of 1958 Douglas had a DC-8 order book with 133 orders. A new factory was built at Long Beach California and the DC-8 prototype first flew in May 1958. The first airline to put the DC-8 into service was Delta Airlines in September 1959 starting a long association with the jet which saw Delta operate many variants over the years. By the mid- sixties several different variants had been made available but the most extreme was the Super 60s range. Long fuselage stretches enabled these new models to carry up to 269 passengers more than any other airliner until the Boeing 747 arrived. By the time DC-8 production ceased in 1972, 556 examples had been made. From 1967 onward following the merger with McDonnell they would be known as the McDonnell-Douglas DC-8 and it was under this name that many were later re-engined with the large CFM56 turbofans to reduce noise and fuel consumption allowing them to continue in service up to this day.

1965 saw the first flight of the twin-engine DC-9, originally conceived back in 1962 as a short to medium range airliner the DC-9 had two rear mounted engines and seating for around 80 passengers. As with the DC-8, Delta Airlines were the first to put the new Douglas into service when it started operations in December 1965. Delta would go on operating aircraft from the DC-9 family until 2014. With the merger in 1967 the DC-9 family was renamed the MD80 and then MD90 series with the MD95 series being sold as the Boeing 717 after the Boeing takeover in 1997. Of all the variants 2441 were built over a production period of 41 years, 976 built under the Douglas banner. The original DC-9-10 could carry 80 passengers the MD90 had been stretched to the point where 172 could be carried.

The final jet airliner to carry the DC name plate was the wide-body three engine DC-10. Started as a Douglas project in 1966, by the time of its first flight in 1971, the company had become McDonnell -Douglas and it flew and was produced as the McDonnell-Douglas DC-10. There are now no passenger DC-10s flying but several companies still use the big wide-body as a freighter. American Airlines were the launch customer for the DC-10 entering service in 1971. The last passenger operator was Bangladesh Biman who retired their last example in 2014.

For 46 years the Douglas name was up among the great aircraft manufacturers and then for a further 30 years it shared its name with McDonnell. After the Boeing takeover and the rebranding to delete the Douglas name you might be excused for thinking that was the end for the company set up by Donald Douglas back in 1921. There is however one small vestige of that great company remaining. Remember the new logo they introduced after the US Navy completed its circumnavigation of the globe? Boeing have adapted that logo to form the current Boeing corporate badge !

‘till the next time Keith

Registered Charity No. 285809