With the recent Rolls- Royce announcement that they are acquiring an ex Qantas Boeing 747 for use as a flying engine testbed, Keith Bradshaw takes a look back at some of the other aircraft used for engine testing in the past.

Although not that commonplace these days due to most “new” engines being developments of older well tried examples, testing a new engine on the wing is not a new procedure. Back in the early days of the jet and Turbo-prop engines manufacturers had no alternative but to nail their new designs onto a suitable airframe and give it go! Interestingly because these designs were the very first jets the only airframes available to test them on were originally piston powered. This led to some quite bizarre combinations, five engine Boeing B17s and Lancasters with two Merlin engines and two jets or another five engine set up were commonplace. There were no computer models or indeed computers available back in the 1950/1960’s when the number of new jets coming onto the market was at its peak. Lots of different companies were eager to produce a successful engine and get their slice of the lucrative future market, the piston engine for large aircraft was now history.

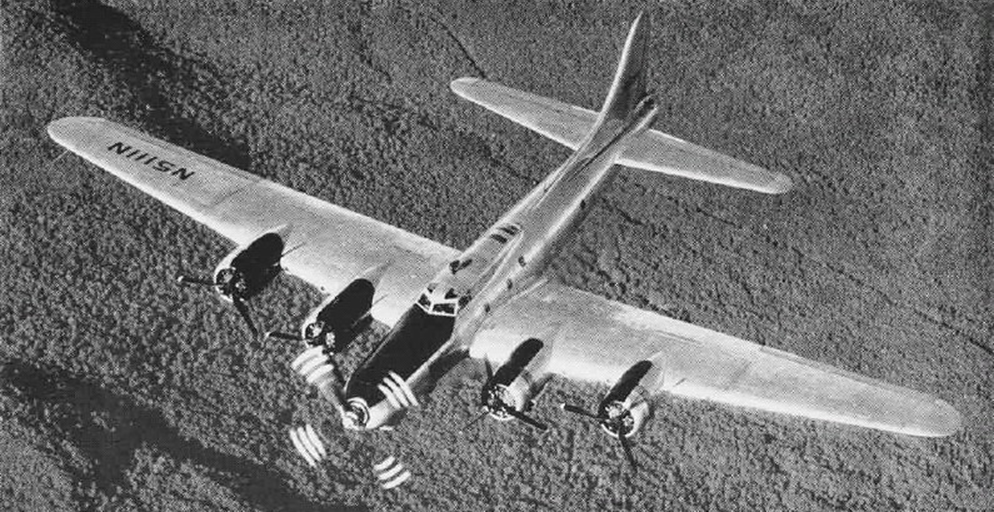

The US company Pratt and Whitney had started to develop their T-34 Turbo prop for use on future large transport planes. Their choice of test bed was to be the ubiquitous Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress. The subject aeroplane kept its own four piston engines and the T-34 was grafted onto its nose making a very unusual, some would say ugly sight.

This engine became a success and was used in several large military aircraft made in the US, also powering the civilian Guppy transport aircraft used for outsize freight. The B-17 that was used for these trials was eventually retired to a museum in the US and converted back to a static exhibit with its original nose refitted. Some years later she was sold on and restored to airworthy status as a warbird. In 2008 this B-17 painted as “Liberty Belle” visited Europe and spent a short time at Duxford parked on the ramp alongside Sally B. After returning to the US she continued to appear on the air show circuit until a few years later in 2011 she was to force land in a field due to an engine fire. All the crew escaped and the fire initially was not too severe but sadly by the time the fire trucks arrived and realised they could not cross the field to reach her it was too late and Liberty Belle was destroyed.

In the UK there were many jet engine manufacturers, Armstrong Siddeley with their Mamba, Sapphire and later Viper engines, Bristol Siddeley with their offerings of Gyron, Proteus and later the Olympus and the Pegasus which would go on to power the revolutionary Harrier jump jet. Aircraft manufacturer de Havilland also had their own engine division making such well known engines as the Ghost and Goblin for their Vampire, Venom and Comet airliner. Napier who had made the massive Sabre piston engine for the World War 2 Typhoon, were hoping to get into the jet business with their Eland.

Rolls Royce however were leading the field with the first RAF fighter jet the Meteor powered by their Derwent engine. It was this engine they hoped to develop into the more powerful Nene jet. Testing took place using a Vickers Viking which had its Bristol Hercules radial engines replaced by two Nenes. Also in use at the same time was an Avro Lancaster which had its outer Merlins replaced by the jets. Although a fairly successful engine the Nene was not widely used in the UK but sold well abroad, including when the government of the day decided to freely pass on the design to the USSR and thousands of Soviet copies were built to power the MIG 15 fighter.

One use for the new engine in the UK was with Avro’s who fitted it onto their new Avro Ashton jet airliner. Derived from the Avro Tudor this new airliner was powered by four Nenes but only a few aircraft were made as its design was technically far behind that of the other new UK jet airliner the Comet. Subsequently a couple of Ashtons were used by various manufactures as test beds for their new engines. Indeed Rolls-Royce made use of one to test its Conway and Avon jets by fitting an example of the new engines in a pod below the centre fuselage. The forward fuselage of this very aircraft can now be found at the Newark air museum, it is the sole remaining part of an Avro Ashton. Another example was used to test the Olympus engine being made by Bristol Siddeley for fitment into the Vulcan V-Bomber. Two Olympus engines were fitted on pylons outboard of the Ashton’s Nenes. The ironic thing about this, is it was a Vulcan that in years to come would be fitted with a Concorde Olympus engine under its fuselage for flight testing.

It had been known for sometime that a Turbo prop ( basically a jet engine optimised to using its power to drive a propeller and not just producing jet thrust) was the most efficient form of propulsion for low to medium altitude flight, hence the race was on to produce a viable example of this form of powerplant. Rolls-Royce had the first flying example in their Trent engine which was a development of the early Whittle jet. Two of these engines were fitted into a Gloster Meteor which became the world’s first Turbo prop powered aircraft to take to the sky. From these trials Rolls developed the world’s first successful production turboprop the Dart, more of which later.

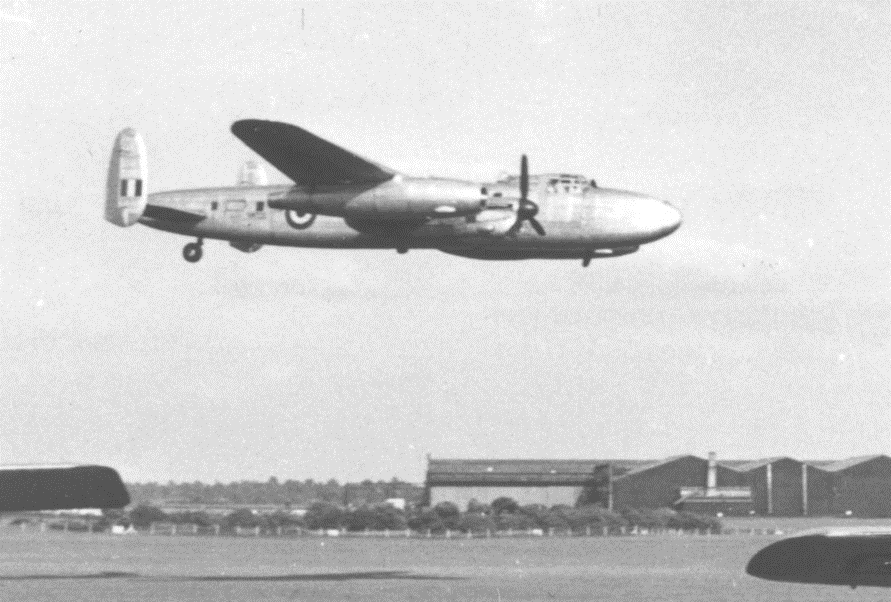

Armstrong Siddeley had been developing a powerful engine for many years and by the early 1950’s they were testing their Sapphire jet on the wing of a Lancaster. This impressive engine went on to power early marks of the Hunter and Victor before becoming the sole powerplant for the Gloster Javelin. Later marks of the Javelin had the developed version of the Sapphire which included re heat. Sadly for Armstrong Siddeley Rolls-Royce had been developing a competitor to the Sapphire in the shape of the Avon, This was much more capable engine and took a large share of the market the Sapphire was intended to fill, for example all subsequent Hunters were Avon powered as was the Javelin’s successor the Lightning.

The Lancaster had proved very popular as a test mount but something more modern and representative of present day aircraft was needed. An aeroplane that fitted the bill very well was the Airspeed Ambassador. The last of the large British built piston airliners Airspeed made just 23 of these elegant aeroplanes. The first three were initially kept by the manufacturer as prototype and test aircraft and it was one of these that was utilised by several engine companies to test their wares. Built with two Bristol Centaurus piston engines the Ambassador was reengined with several types of turboprop such as the Bristol Proteus, Napier Eland and Rolls-Royce Dart. The Proteus went on to power the Britannia but the Eland failed to sell well in the UK, it’s main claim to fame being the powerplant for the unique Fairy Rotordyne. It did however find use in the USA and Canada as the engine for the Convair 640. When Rolls-Royce took over Napier in 1961 Eland production was stopped. The Rolls-Royce Dart went on to be the most successful British turboprop engine of all time.

Rolls-Royce had been working on their Dart engine as a power plant for the proposed Vickers Viscount airliner. The Dart was first run in 1946 and remained in production until 1987 its first flight being in the nose of a Lancaster in 1947. Further testing took place using a Vickers Wellington reengined with two Darts. BEA was keen to become the launch customer for the Viscount which would become the world’s first turboprop powered airliner, however it was worried about the new untried engines and also how it’s crews who had only ever flown slow piston engines would adapt to the new way of operating. To this end they converted two of their cargo DC-3 Dakotas to Dart power in a sort of “try before you buy” scenario. This conversion allowed the Dakotas to fly at 200mph at 25,000 feet whereas the original aircraft bumbled along at 160mph at 7000 feet. These figures go a long way to explain the learning curve not just the pilots but ground engineers, flight planners and management had to get under their belts before the Viscounts arrived. Stories abound of those testing days when ATC could not believe a Dakota was talking to them from 20,000 feet or en-route crews in the airliners of the day such as the DC-6 being told to look out for a Dakota overtaking them from above! Due to the heights they could now fly the crew had to wear Oxygen masks as the dear old Dakotas were not pressurised never having been designed to fly so high.

Over a period of time and with Government intervention Rolls-Royce took over all the other engine manufactures to become the UK’s sole aircraft engine producer. As such they began in the late 1960’s developing a high bypass ratio jet engine. Up to now all the engines produced had been low bypass which meant all or most of the air coming in the front of the engine went through the engine and was burnt with fuel to produce thrust. However it could be shown that if some of the air bypassed the core engine and was ducted around the outside, meeting the jet thrust at the rear, a greater overall thrust could be produced. The effect of passing this cold air around the outside of the engine also kept the core cool which meant it could run more efficiently using less fuel. There was also the added advantage that the bypass air acted as a sound muffler so the engines were quieter. As with all good ideas there was a problem and that was the ability to make the large fan blades at the front sufficiently robust to stand the pressures put upon them. The engine Rolls was developing was the RB211 large fan engine. Such a radical new engine had to be air tested and being so large there was not a wide choice of airframes it would fit onto. In the end the MOD arranged for the RAF to lend Rolls a VC10. This would have both the left hand Conway engines, their nacelles and all the support frame removed and replaced by one RB211

The trials proved that Rolls had a winner in the RB211 and it became the engine of choice for the new Lockheed L1011 Tristar airliner. RB211 engines went on to power many of the world’s wide body aircraft and it was later further developed into the Trent which has become a world beater for Rolls- Royce powering many of the latest Boeing and Airbus jets of today. After the flight trials had finished the original plan called for the VC10 to be returned to its normal four engine fit and given back to the RAF. Sadly it was deemed the cost for this was too high and the aeroplane was eventually scrapped.

Obviously buying your own aeroplane for testing is not cheap so I wonder what Rolls-Royce have in mind for their new Boeing 747 when it arrives. One project they are unlikely to use it for is developing one of their small helicopter engines into a hybrid power plant. Rolls have teamed up with Britten-Norman and the Cranfield Institute of Technology to develop an electric hybrid engine for the Islander. The plan calls for the aeroplane to have a range of 100 miles using electric power alone and will be ideal for the short hops these aeroplanes presently make around the Scottish islands, first flight is planned for 2022.

So there we have it, a short look back at jet engine testing over the decades. Finally never wanting to pass up the chance of a picture of a Constellation we close with this shot of an ex Air France Constellation that was converted with this Heath-Robinson affair, to air test the French built Turbomeca Bastan turboprop. The aeroplane has sat at the Musee d’Air et Espace at Le Bourget for many decades and is under long term restoration, sadly back to a stock Air France example, c’est la vie!

‘till the next time Keith

EDITORS NOTE:

The electric Islander is being developed under project Fresson**. The exact configuration has not been finalised yet and may involve hybrid power. After the Islander they are looking to move on to a Viking Twin Otter. But they will not be the first as the Harbour Air ePlane, a converted de Havilland Canada Beaver, flew for the first time on 12 December 2019.

** The Fresson Project takes its name from Scottish pioneer aviator Captain Ernest Edmund ‘Ted’ Fresson, OBE (1891-1963). Born in Surrey, Fresson trained to be an engineer and worked in China both before and after WW1. In 1918 he trained to be a pilot in the RFC. In 1927 Fresson returned from China to the UK and gave aircraft joy rides to the public. This led to him starting Highland Airways in 1933 providing scheduled airline flights to the Highlands and Islands of Scotland – a company that was eventually nationalised as part of British European Airways in 1947.

Registered Charity No. 285809